What Is Formalism in the Philosophy of the Arts?

Beginnings

"L'art pour 50'art"

The development of Formalism was informed by the doctrine of "fifty'fine art pour l'fine art" ("art for art's sake"), first used by Victor Cousin, a French philosopher, during the early on 1800s. Subsequently, the French novelist Théophile Gautier used the phrase to describe his novel, Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835); past the mid-1800s, a number of literary and visual artists were promoting the idea that art existed solely for its ain sake, and should not serve any social or moral purpose.

The artist James McNeill Whistler said that "art should exist independent of all claptrap - should stand solitary." As a leading figure of both the Artful motion and Tonalism, Whistler'due south "nocturnes", such as Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Erstwhile Battersea Bridge (c. 1872-75), became influential exemplars of a Formalist approach. Critic Clive Bell would later depict Whistler as being among those "who made form a ways to aesthetic emotion and non a means of stating facts and conveying ideas."

The Emergence of Critical Formalism

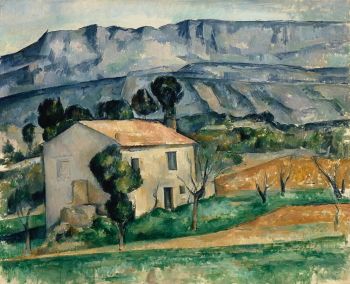

Formalism every bit a critical approach - rather than equally a mantra amongst artists - began to sally during the late 1800s, especially in response to Post-Impressionism. This shift was informed by philosophy as much as by the pronouncements of artists. The philosopher Hippolyte Taine, for example, in his The Philosophy of Fine art (1865), described a painting as "a colored surface, in which the various tones and diverse degrees of lite are placed with a certain choice; that is its intimate being." The Post-Impressionist Maurice Denis, in his "Definition of Neo-Traditionalism" (1890), stated that "a moving-picture show, before it is a film of a battle equus caballus, a nude adult female, or some story, is essentially a apartment surface covered in colors arranged in a sure social club." Denis'due south much quoted text became foundational to the early emergence of critical Ceremonial, though in some respects its remit was narrow, merely acknowledging the flatness of the picture airplane at a time when artists such as Paul Cézanne had already developed radical new approaches based on that concept.

The critic Alois Riegl was likewise of import in establishing Formalism as a disquisitional tradition, as well as establishing art history as field of study. In works such as his Spätrömische Kunstindustrie ("Late Roman Fine art Manufacture") (1901), Riegl developed the concept of a Kunstwollen, or a cultural or period style, unified by certain mutual stylistic traits. Riegl's writing influenced a number of later 20th century scholars such equally Walter Benjamin, Erwin Panofsky, and Otto Rank.

Clive Bell and Roger Fry

Members of the innovative Bloomsbury group, Clive Bell and Roger Fry both helped to pioneer and develop the theory of Formalism in the early 20th century. Every bit an artist and a critic, Fry was influenced by Paul Cézanne; as a curator, he played a leading role in introducing Post-impressionism to Anglophone audiences. His exhibition "Manet and the Post-Impressionists", which opened in London in 1910, included works past Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin.

In the exhibition brochure, Fry wrote of "the revolution that Cézanne has inaugurated...His paintings aim not at illusion or abstraction, but at reality." According to art historian Elizabeth Berkowitz, the show was "visited by most 25,000 individuals over the course of two months [and] was also a commercial success." Fry's exhibition besides gave Postal service-Impressionism its proper name; Fry went on to promote a number of at present canonical painters including Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Léger, Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Miró.

Fry's involvement in Mail service-Impressionism and Cubism reflected a passion for creative stylistic which emphasized formal furnishings over figurative or narrative value. According to art critic Michael Fried, the "core of [Fry's] then-chosen formalist esthetics [was] the conviction that all persons capable of experiencing esthetic emotion in front of paintings...are responding when they practise so to relations of pure form - roughly, of ideated volumes in relation both to i another and to the surface and shape of the canvas - rather than to whatever dramatic expressiveness the work in question may be held to possess."

Fry's views were compatible with those of the critic Clive Bell, who would get the nigh influential vox in establishing Formalist theory. His pioneering work Art (1914) argued for what he called "meaning class," posing the question: "[w]chapeau quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Farsi basin, Chinese carpets, Giotto'southward frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cézanne? Only one answer seems possible - meaning form. In each, lines and colors combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions."

For Bell, Paul Cézanne'south works exemplified the idea of "significant form." He called the artist "the Christopher Columbus of a new continent of form," and further advocated for the importance of his work in Since Cézanne (1922). Bell dismissed what he called "Descriptive Painting," declaring that, while "portraits of psychological and historical value, topographical works, pictures that tell stories" interested us, they were "not works of fine art. They go out untouched our artful emotions." In contrast Bell wrote, "Cézanne fix himself to create forms that would express the emotion that he felt for what he had learnt to see...Everything can be seen equally pure form, and behind pure course lurks the mysterious significance that thrills to ecstasy. The residual of Cézanne's life is a continuous effort to capture and limited the significance of form."

The Emergence of Brainchild

Formalism's emphasis upon the composition of formal elements paralleled and furthered the rise of abstraction. The connectedness could exist seen as early every bit the near-abstraction of Whistler's Nocturne in Blackness and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1875) or Cezanne's final landscapes. Edifice upon Cezanne's emphasis upon "the cylinder, sphere and the cone" as the visual components of the natural world, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque developed Cubism's multiple perspectives and fractured forms. In Du Cubisme (1912), Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, the leaders of Salon Cubism, wrote that Cézanne's work "proves without uncertainty that painting is non - or non any longer - the art of imitating an object past lines and colors, but of giving plastic [solid, but alterable] course to our nature."

In 1913, Kazimir Malevich developed the principles of Suprematism, an abstract art equanimous of a limited number of geometric forms. As he later recalled, "[i]northward the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the expressionless weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the foursquare." David Bomberg, a pioneer of abstraction in Britain, described his work on similar lines: "I appeal to a sense of grade - where I use naturalistic form I take stripped information technology of all irrelevant thing...My object is the construction of Pure Form." His works, such as The Mud Bath (1914), depicted the human figure as a geometric shape, a process which he described as "searching for an intenser expression."

The Expressiveness of Course

Man Ray, the USA-born Dadaist and Surrealist, issued a statement in 1916 for The Forum Exhibition of Modernistic American Painters at the Anderson Galleries in New York. Including work by sixteen American painters, such as Arthur Pigeon, Charles Sheeler, Thomas Hart Benton and Marsden Hartley, the exhibition was meant to advance the idea of a North-American tradition of advanced fine art, building on the momentum of the famous Armory Prove of 1913. Man Ray wrote that: "[t]he creative force and the expressiveness of painting reside materially in the color and texture of pigment, in the possibilities of form invention and organization, and in the apartment airplane on which these elements are brought to play." The artist, meanwhile, "is concerned solely with linking these absolute qualities directly to his wit, imagination, and experience, without the become-between of a 'subject.'"

In 1916 Man Ray besides privately published A Primer of the New Art of Two Dimensions. His treatise failed to find a post-obit and Man Ray was to become best known for his subsequent Dada and Surrealist works, and as a lensman. However, as art historian Francis Thousand. Naumann wrote, the primer presented "the basic tenets of a remarkably prescient Formalist theory, one that contains the seeds of a critical approach that would not be fully explored in American fine art for some xl years, non until the so-chosen second generation of Formalist critics applied their analysis to the paintings of the Abstract Expressionists in the 1940s and 1950s. The three basic tenets of Ceremonial consort past these critics can be summarized as follows: (i) primary interest in the structural order of a work of art; (2) purity of the medium; and (3) integrity of the flick plane. All three of these concerns are either directly stated or implied in Man Ray'southward writings."

Cloudless Greenberg

In the 1940s, Cloudless Greenberg defined and promoted the central concepts of Formalism to such a degree that his name became synonymous with the term. According to the poet and critic John Yau, "with his 1939 essay 'Advanced and Kitsch' Greenberg began to develop his brand of Formalist theory regarding innovative modernistic art...[He] made 3 points. Commencement, Modernism is divers by self-criticality...2nd...avant-garde painting clarifies its essential uniqueness as a two dimensional, flat surface...Third, brainchild is more than avant-garde than representational art."

Many of Greenberg'southward subsequent essays, including "Towards a New Laocoon" (1940), "'American Type' Painting" (1959), and "Modernist Painting" (1960) became keystones of Formalism. Each essay adult a farther tenet of the school. For example, "'American Type' Painting" (1959) advanced the works of the Abstract Expressionists, including Hans Hoffman, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Arshile Gorky, and Adolph Gottlieb, pinpointing the specific figures and styles that informed each artist. By discussing how each artist'south painterly language evolved, Greenberg was able to indicate how Abstruse Expressionism exemplified purity of course and purpose in painting.

In "Modernist Painting" (1960), Greenberg fully defined his concepts of flatness and medium-specificity, and described how Modernism, in his words, "used fine art to telephone call attention to art." He defined medium-specificity equally "the unique and proper area of competence of each fine art...all that was unique in the nature of its medium." He divers painting's unique qualities every bit "the apartment surface, the shape of the support, the properties of the pigment." In Greenberg's view "Manet's became the beginning Modernist pictures by virtue of the frankness with which they alleged the flat surfaces on which they were painted."

Artists and Formalism

Every bit Clement Greenberg's Ceremonial became a dominant force in the 1940s, the leading Abstract Expressionists, Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, wrote a letter in The New York Times, which stated: "We do non intend to defend our pictures. They brand their ain defense force. We consider them clear statements...We refuse to defend them not because we cannot. It is an easy matter to explicate to the befuddled [critics] that The Rape of Persephone is a poetic expression of the essence of myth...the bear on of elemental truth." The two artists essentially believed that any try to deconstruct and subsequently explain an abstract work of fine art was to strip information technology of its intrinsic value. The ultimate meaning of an abstruse artwork was to exist found in its shapes, colors, and lines, and through the acceptance that, according to Rothko, "art is an adventure into an unknown world." Yet, at the same time, Rothko and Gottlieb also felt that a traditional classical subject, taken from Greek myth, could be expressed through that elemental form and abstract composition. Every bit they noted, "[w]e favor the elementary expression of the complex idea. Nosotros are for the large shape because it has the bear upon of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the moving picture airplane. We are for apartment forms considering they destroy illusion and reveal truth."

"School of Greenberg"

As John Yau notes, "Greenberg's Formalist theory was understandably attractive to younger critics and art historians considering he seemed to be turning fine art history into a scientific method...In doing so, he is challenge to exist objective rather than subjective." Greenberg's influence is borne out in the writing of a number of younger critics, sometimes called the "School of Greenberg," who rose the prominence during the 1960s-80s, including Michael Fried and Rosalind Krauss. Co-ordinate to the critic Michael Schreyach, "the years spanning the publication of Clement Greenberg'south 'Towards a Newer Laocoon' in 1940 to Fried's 'Fine art and Objecthood' in 1967 witnessed the consolidation of Formalist criticism as the well-nigh intellectually exacting - and institutionally powerful - framework for understanding modernist art in the United States."

Michael Fried became a leading proponent of Formalism, arguing in "Art and Objecthood" (1967) against what he called the "theatricality" of Minimalism. Influenced by Greenberg, he extended Formalist theory in advocating for the paintings of Kenneth Noland and Frank Stella, and for the sculptures of David Smith and Anthony Caro.

Fried has continued to defend and promote the tenets of Formalism, as in his 2001 lecture "Roger Fry's Formalism," which reconsidered Fry's approach in conjunction with Greenberg's. As Fried put information technology, "[o]ne may deplore the fact that critics such every bit Fry and Greenberg concentrate their attending upon the formal characteristics of the works they talk over; just the painters whose work they most esteem on formal grounds - e.yard. Manet, the Impressionists, Seurat, Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Léger, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Miró - are amongst the finest painters of the past hundred years."

By contrast, other proponents of Greenbergian Formalism, such as Krauss and Barbara Rose, were to move abroad from the limitations of Greenberg's arroyo later in their careers. As the art historian Donald Barton Kuspit notes, "[d]espite her adoption of Greenberg's focus on the object and its cloth qualities, [Krauss] repudiated Greenberg'south Ceremonial for its lack of 'method,' in contrast to her own use of theoretical models."

Critics who Defied Formalism

Several critics during the era of Abstract Expressionism challenged Greenberg's Formalism. A leading rival, Harold Rosenberg, developed the term "action paintings" to draw Jackson Pollock's drip paintings, while arguing that "[f]ormal criticism has consistently buried the emotional, moral, social and metaphysical content of modernistic art nether blueprints of 'achievements' in handling line, colour, and form." Greenberg responded by characterizing Rosenberg's approach every bit involving "perversions and abortions of discourse: pseudo-description, pseudo-narrative, pseudo-exposition, pseudo-history, pseudo-philosophy, pseudo-psychology, and - worst of all - pseudo-poetry." Curator Norman Kleeblatt has called the rivalry betwixt the two men "the foundational dialectic of the era," adding that "many observers one-half a century ago viewed the opposed perspectives of Rosenberg and Greenberg as the but approaches to contemporary fine art...either a Formalist or an existentialist view."

While Leo Steinberg and Thomas B. Hess also raised challenges to Formalism, arguably no critic presented more than consistent opposition to the school than Robert Rosenblum. Rising to prominence later on the heyday of Abstruse Expressionism, Rosenblum proceeded to redefine the history of mod art by stretching the historical boundaries of modernism to include 18th-century Bizarre and Neoclassicism.

In his essay "The Abstract Sublime" (1961) Rosenblum redefined the Abstract Expressionists, Clyfford Still, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman as proponents of what he chosen the "Abstract Sublime," heirs to the Northern Romantic Tradition. "[T]hese 4 masters of the Abstract Sublime," Rosenblum proposed, "have rejected the Cubist tradition and replaced its geometric vocabulary and intellectual structure with a new kind of space created by flattened, spreading expanses of light, color and plane. Yet information technology should non be overlooked that this...is not only determined by formal needs, but also past emotional ones that...suddenly seem to represent with a Romantic tradition of the irrational and the crawly every bit well equally with a Romantic vocabulary of boundless energies and limitless spaces." This emphasis on the emotional content of the work was in stark and deliberate contrast to the Formalist ideology.

Concepts and Trends

"Truth to Materials"

An emphasis on the materiality of an artwork, divers in terms of "truth to materials," was a primal tenet of Ceremonial, also as a cardinal concept within 20th-century art in general. In 1934, the British sculptor Henry Moore wrote: "[e]very fabric has its ain individual qualities ... Stone, for case, is hard and concentrated and should not be falsified to expect like soft flesh ... It should go on its hard tense stoniness."

This emphasis upon an artwork's materials had its origins in the 19th century. It informed the Arts and Crafts motion, amongst others, while the Victorian critic John Ruskin wrote that "[t]he workman has not done his duty, and is not working on safe principles, unless he ... honors the materials with which he is working ... If he is working in marble, he should insist upon and exhibit its transparency and solidity; if in fe, its strength and tenacity; if in gold, its ductility..."

Clement Greenberg extrapolated his famous concept of medium-specificity or medium "purity" from this wider Formalist principle. In his essay "Modernism" (1960) he argued that "to eliminate from the effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably exist borrowed from or by the medium of any other art" was a central aim of modernistic fine art. Flatness was the defining formal chemical element of the painting for Greenberg: "flatness lonely was unique and exclusive to pictorial fine art...the only condition painting shared with no other art."

Ironically, while the concept of "truth to materials" informed the evolution of Formalism, it also greatly informed the rise of Minimalism, which departed from Abstract Expressionism in its utilize of not-creative and industrial materials and processes, probing the limits of the artwork as a 'composed' entity. Greenberg was to dismiss Minimalism equally "Novelty," while Michael Fried in his "Art and Objecthood" argued confronting Minimalism'due south "theatricality."

Formalism and Philosophy

Formalism was influenced by a number of philosophical concepts and trends, particularly fatigued from the Plato's concept of ideal forms, and from the 18th-century High german philosopher Immanuel Kant'southward concept of "purposive course."

Using the discussion "eidos, "pregnant "visible form," interchangeably with the word "idea," Plato argued that truth resided in a realm of perfect forms which utterly embodied the ideals which evoked those forms. By comparison, everyday objects were mere shadows mimicking the ethics; for example, a beautiful object was but an imitation of the ideal form of Beauty. In his 'allegory of the cave,' Plato described this concept by developing the metaphor of prisoners held in a cave since babyhood. Their merely feel of reality was the shadow of things moving on the wall earlier them, reflections cast by their own movements, lit up by the burn down behind them. True noesis meant leaving the cave and walking into the sunlight, a metaphor for entry into the realm of pure forms.

Clive Bell's Formalist theories echoed this relationship betwixt the universal and the particular: he wrote that Paul Cézanne's work manifested "a sublime architecture haunted by that Universal which informs every Particular. He pushed further and further towards a consummate revelation of the significance of form....His ain pictures were for Cézanne nothing just rungs in a ladder...The whole of his later on life was a climbing towards an ideal." This clarification of the particular or 'concrete' as 'rungs in a ladder' by which the artist climbed towards an ideal strongly evokes Plato's philosophical stance.

The High german philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment (1790), argued that "the proper object of the pure judgment of taste" was "the delineations [in the] composition." Every bit the contemporary philosopher Donald W. Crawford notes, "for Kant, form consists of the spatial...organization of elements: effigy, shape, or delineation, adding that "[i]n the parts of the Critique of Judgment in which form is emphasized equally the essential aspect of beauty, Kant is consistently a pure Formalist." Clive Bell'southward concept of "significant form" was influenced by Kant's concept of 'purposive form." Clement Greenberg besides noted Kant'south importance, noting that, "[b]ecause he was the get-go to criticize the means itself of criticism, I conceive of Kant as, the first real Modernist."

Flatness and Medium-Specificity

In developing his theory of Formalism, Greenberg not but defined the elemental formal components of canvas painting, but also developed the interrelated concepts of flatness and medium-specificity. Flatness, or what Greenberg chosen painting'southward "literal ii-dimensionality," was, he argued, "unique and sectional to pictorial art...the merely condition painting shared with no other fine art." He defined medium-specificity more by and large as "the unique and proper area of competence of each art [that] coincided with all that was unique in the nature of its medium."

Greenberg felt that painting'south medium-specificity, which was sometimes dubbed 'purity,' would eschew any attempt to suggest three-dimensional or sculptural form. As such, just an abstract painting, refusing 3-dimensional illusion and therefore refusing context, narrative, or figuration, could obtain medium-specificity. As Greenberg'south Formalism was an examination of an artist'due south ability to visually residual the elemental forms on the sheet, it was too a judgment of that painting's purity of medium and style. It was partly for this reason that Greenberg championed the work of Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko, pioneers of Abstruse Expressionism and Colour Field painting.

Literary Formalism

Though it has followed its ain path of development, literary Formalism too emerged in the early 20th century, initially with the emergence of Russian Formalism. In 1914 in St. Petersburg, the OPOJAZ Club for the Written report of Poetic Linguistic communication was founded, emphasizing a 'scientific' or formal approach to poetic language and literary devices. As the scholar Victor Erlich wrote, the school "was intent upon delimiting literary scholarship from contiguous disciplines such as psychology, sociology, intellectual history, and...focused on the 'distinguishing features' of literature, on the artistic devices peculiar to imaginative writing."

While it was focused on language, the movement paralleled the development of Russian Futurism, an avant-garde art movement forged in literary circles. Though the Soviet Commissar for Instruction suppressed Russian Ceremonial in 1930, it became an important forerunner to later Formalist literary approaches, including structuralism and post-structuralism. According to the literary scholar Douwe Fokkema, "[almost] every new schoolhouse of literary theorists in Europe takes its cue from the 'Formalist' tradition, emphasizing different trends in that tradition and trying to establish its own interpretation of Formalism as the but right one."

Later Developments

The influence of formalism began to decline by the 1960s, as movements inimical to its methods, such equally Popular Fine art, Minimalism, Neo-Dada, and Performance Fine art, emerged as dominant forces. Moreover, according to Michael Schreyach, "for some mail service-Abstruse Expressionist artists, the modernism endorsed by Greenberg and Fried seemed express and limiting... Consequently there emerged diverse artistic practices and theoretical frame-works... rejecting Formalist autonomy and...reconnecting creative practice to the social and political dimensions of 'everyday life'." According to Donald Barton Kuspit, "[b]y the terminate of the 20thursday century, Hilton Kramer, one-time fine art critic for The New York Times and editor of the conservative journal The New Criterion, remained the 1 major convinced Greenbergian."

It is important to note, however, that Formalism continued to inform near all critical approaches to modern fine art beyond the twentyth century and will survive in the aforementioned manner beyond the 21st, because it taps into such an elementary aspect of all artistic interpretation: the simple recognition that formal qualities such as the way lines and colors interact, the texture of paint or a sculpted surface, the way bodies or objects are arranged in conceptual or functioning art, and and so on and so on, are hugely pregnant to the meaning of an artwork Near modernistic art historians and scholars take up formal assay equally a vital method for analyzing and agreement artworks, just their formal analyses is generally framed by an sensation of cultural or historical context, making information technology distinct from Formalism.

Morevoer, in the 21st century, a more strictly defined Formalist approach continues to spark interest. According to fine art historian David East. W. Fenner, the philosopher Nick Zangwill "has washed more than any person recently to resuscitate artful Formalism" notably through his 2001 text The Metaphysics of Dazzler. Zangwill has outlined his position equally a defense force of "moderate Formalism," which he farther describes as "determined solely past sensory or physical properties - and so long equally the concrete properties in question are non relations to other things and other times." In Berlin in 2014, the JFK Institute for N American Studies held a console on the Goals and Limits of Ceremonial. The accompany publication described "a renewed interest in Formalism as a self-critical theory, i that is non merely attentive to its own historical development (going back farther than 1940), just also alert to its possible methodological restrictions."

The virtually recent 'revival' of Formalism was dubbed "Zombie Formalism" by fine art critic Walter Robinson in 2014. Around 2011, a boom in the fine art market was fueled by an influx of collectors who were primarily interested in contemporary art as a style of turning a quick turn a profit. More accurately dubbed "art flippers," these investors purchased the works of immature artists, such every bit Lucien Smith and Jacob Kassay, and and so quickly "flipped," or resold, the works at art auctions. As art critic Chris Wiley wrote, the "polite, bookish designation...was 'procedure-based abstract painting'...but it was Robinson's 'Zombie Formalism' moniker, with its built-in critique, that really stuck." Robinson explained his term: "'Formalism' because this art involves a straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting...and 'Zombie' because information technology brings dorsum to life the discarded aesthetics of Clement Greenberg."

Within a few years the market place collapsed, as art critic Tim Schneider describes: "[t]he most infamous example of this process was the trajectory of Lucien Smith's Hobbes, the Pelting Man, and My Friend Barney/Nether the Sycamore Tree (2011), an epic-scale landscape painting kickoff sold for $10,000...then bought at sale...in 2013 for $389,000, and finally...reduced to unsellability two years later on." A few artists, including Oscar Murillo, Tauba Auerbach, and Alex Israel, equally Schneider noted, "survived the Zombie Formalist apocalypse to earn a long-term seat at the art earth's table," merely, in general, the movement and its decline made a new opening for art with sociopolitical concerns. The tendency also continues to fuel questions near the value of art and the human relationship of art institutions to fine art markets. Every bit art critic Chris Wiley wrote in 2018, "[i]n an economical sense...zombie ceremonial was perhaps the biggest story of the past decade, transforming the art market and irresolute what it means to be a young artist. It'southward a story about fine art's fraught relationship to finance, and also, I want to argue, about the way debt has become subtly inextricable from discussions of contemporary aesthetics."

Source: https://www.theartstory.org/definition/formalism/history-and-concepts/

0 Response to "What Is Formalism in the Philosophy of the Arts?"

Post a Comment